The Rise and Fall of Autochrome: Pioneering Colour Photography

The Lumière brothers, born in France in 1862 and 1864, grew up playing and learning in their father’s photography studio, where he not only took photos but also produced black-and-white blue sensitive photographic plates that where very similar to the ones we make these days with Zebra Dry Plates. By 1882, after a severe economic crisis, the family business was on the brink of collapse. However, the return of 20-year-old Auguste from military service marked a turning point. With his brother Louis, they developed new machines necessary for the automated production of photographic plates. They innovated a new black-and-white photographic plate known as Étiquettes Bleue, which became a huge success. Within two years, they had hired a dozen employees for production. After their father’s retirement, the brothers dedicated much of their time to moving pictures, patenting their film camera at the end of the 19th century and shooting the first film of workers leaving their factory.

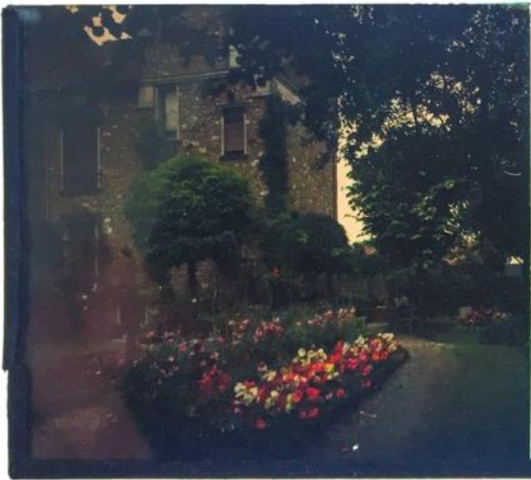

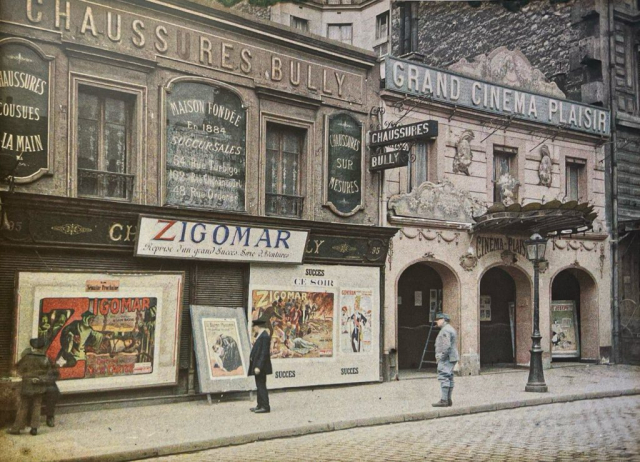

After 1890, the brothers experimented with many existing colour photography techniques, including a bichromated gum process, which was showcased at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. Louis Lumière began contemplating the improvement of Joly and McDonough’s techniques and solving the puzzle of colour photography in 1896, a pursuit confirmed by patents filed in 1900. With his brother’s help, Louis continued researching and developing for three more years. Their long-held dreams, originating from their time studying at the technical school in Lyon, finally came to fruition in 1903 when they succeeded in creating a process that transformed the black-and-white world into a dazzling spectrum of colours. It took an additional four years of industrialization before the first Autochrome plate was ready for the market.

The Concept of Autochrome

1. Technological Principles

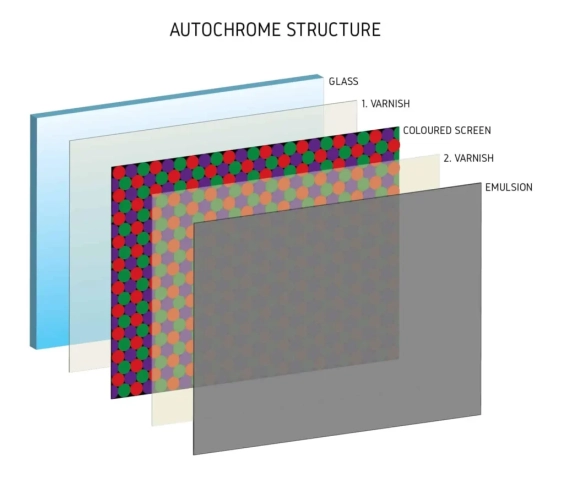

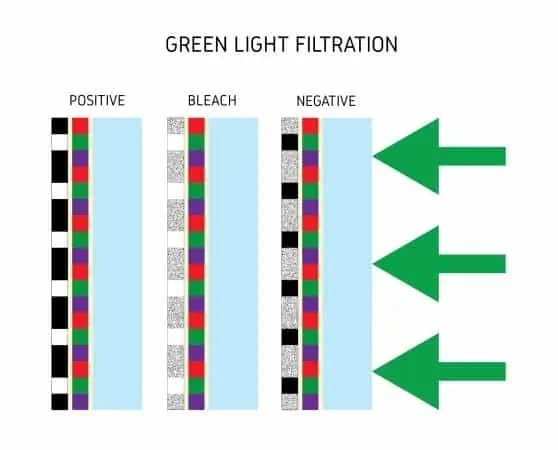

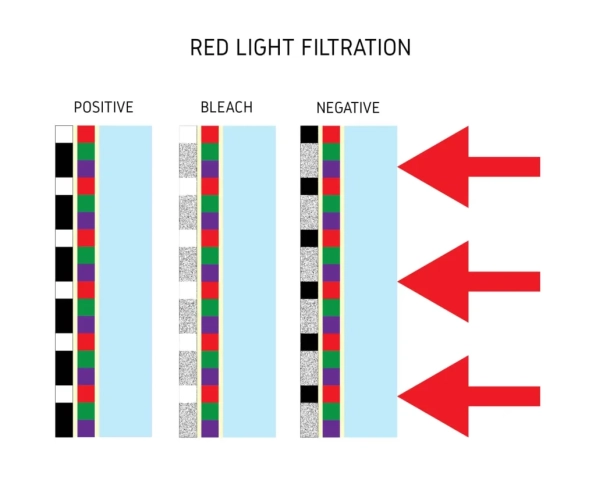

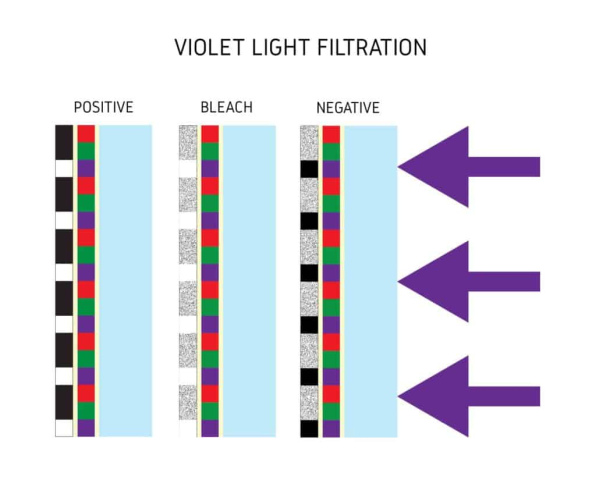

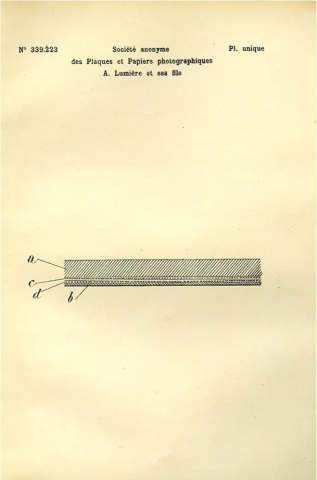

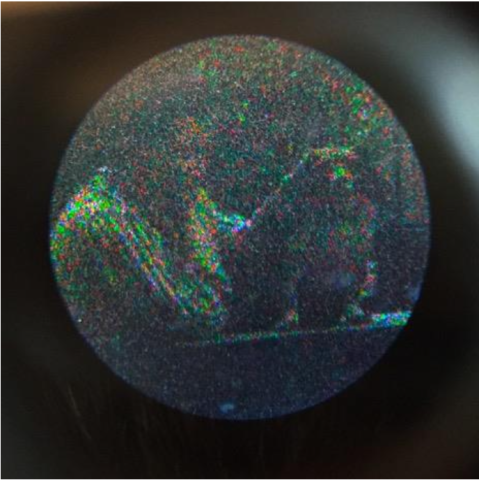

Autochrome is one of the earliest colour photographic techniques, based on the additive colour screen process. It consists of a glass plate coated with a thin layer of adhesive, onto which starch grains dyed in three colours (the colour screen) are sprinkled. The plate is then coated with a protective layer, followed by a light-sensitive emulsion. Before Autochrome, creating a colour photograph required making three separate negatives using three different colour filters. The most significant innovation of Autochrome was its colour screen, composed of microscopic starch grains dyed in three colours: red-orange, blue-violet, and green.

When taking a photograph, the Autochrome plate is inserted into the camera in an unusual way, with the emulsion facing away from the light source. The light first passes through the colour screen, filtering through the dyed starch grains, and then interacts with the silver particles in the emulsion. These dyed starch grains act as tiny filters, each blocking a specific wavelength of light. Due to the glass substrate and multiple layers, exposure times were long, often several seconds. After exposure, the plate is developed in a darkroom, resulting in a positive image. The developed plate can only be viewed using a special device or projector. The positive image behind the screen darkens the coloured grains, which are so small they are invisible to the naked eye, creating an optical additive mixture of the three colours in our eyes, resulting in a photograph with a broad spectrum of colours.

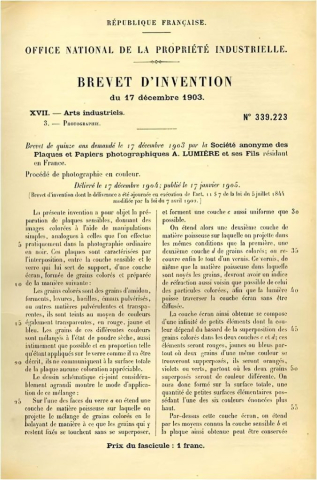

2. Patenting

Autochrome was protected by numerous patents, covering both the production process and potential future applications. The first document, filed with the French National Patent Office, was titled Procédé de photographie en couleur (Colour Photography Process). The application was submitted on December 17, 1903, with a validity of 15 years. It was classified under patent category No. 17 (Industrial Arts), as were all subsequent patents. The protection extended to 25 other European countries, as well as North America, Russia, North Africa, and Australia. The first patent serves as the foundation for all colour plates with randomly arranged coloured grains, made from starch particles, yeast, bacilli, powdered enamels, or other similar transparent materials. While this patent description outlines the early stages of the Autochrome plate, many aspects of the process were still unknown. Part of the description refers to colour mixtures of red, yellow, and blue as subtractive primary colours, which, when applied in two layers, could produce six colours. Such a two-layer arrangement would absorb a great deal of light—one Autochrome plate alone absorbs 90% of the light—making exposure times unmanageably long and the final product impractical to view. However, three additions that were previously unknown gradually became public and were incorporated into the existing patent.

3. Production

The apparent simplicity of Autochrome plates is the result of a complex industrial process required for their production. At every stage, the Lumière brothers faced new challenges and were forced to make compromises. Looking back, we can admire the effort and ingenuity they invested in overcoming these hurdles, and it is worth exploring some of the most difficult and decisive steps toward industrialization in more detail.

- First Challenge: Selecting the Material for Micrograins

After examining most starches under a microscope, Louis Lumière chose potato starch because it was highly light-permeable, absorbed dye well, and was nearly perfectly round. The potato starch grains undoubtedly contributed to the success of Autochrome plates, sparking the imagination with the notion that something so simple could play a major role in the development of photography. The original particles, before separation, varied between 5 and 100 microns, and the smallest ones, which the Lumière brothers needed, accounted for only 2% of commercially used starch. To isolate the smallest particles, Louis Lumière turned to his neighbor Francisque Demure, who lived and worked on the same street, opposite the Lumière factory. It made the most sense that he would become their starch supplier. His company processed starch into dextrin, used in making canvases. To optimize the extraction of microstarch, Demure purchased a new system capable of processing between 14,000 and 16,000 kilograms of potatoes in a 12-hour workday. He created six identical basins, interconnected with valves, allowing water to circulate while the starch settled to the bottom. The extracted starch was then packed into cloth bags and sent to the Lumière factory. There, a special siphon separated the particles ranging from 12 to 16 microns in size, which the brothers needed.

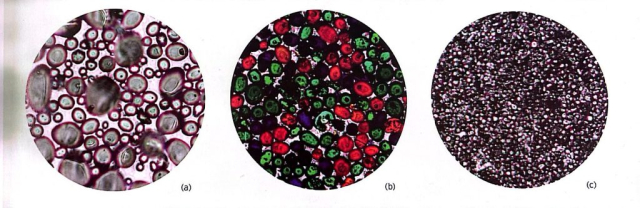

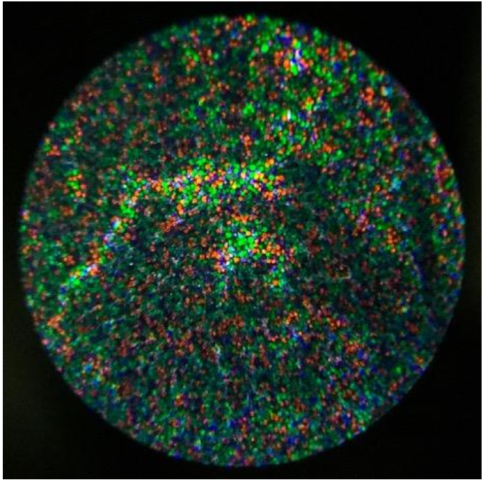

- Second Challenge: Dyeing and Applying the Starch Grains

Most synthetic dyes used to colour the starch grains had been developed only a few years earlier within the emerging field of chemistry. The task was to prepare three differently coloured starch batches in blue-violet, red-orange, and green. Louis Lumière encountered the challenge of ensuring that the dyes adhered well to the grains. Finding the right pigment mixtures was simple compared to the technical difficulties in industrializing the process. In the end, the method proved similar to those described in the literature for preparing filters used in early colour photography.

The grains were first dyed and then mixed in large rotating drums. Once the mixture was ready, it needed to be applied to the glass plate in a single, even layer to prevent clumping or overlapping of grains. The mixture of coloured grains was sprinkled onto the adhesive-coated surface, and a single layer of grains adhered to the surface. This resulted in a density of 8,000 to 9,000 coloured elements per square millimetre or about 200 million grains on a 13 × 18 cm plate.

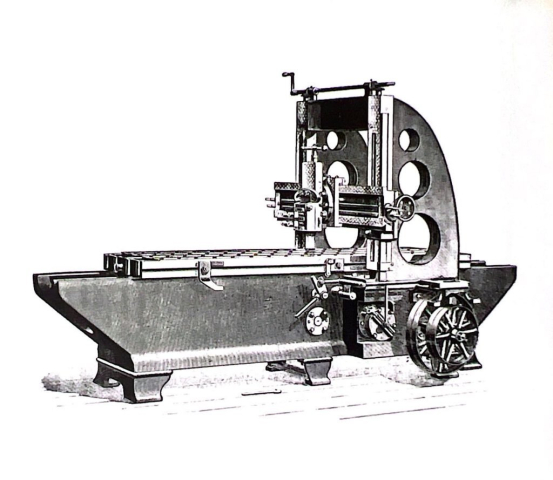

- Third Challenge: Pressing the Grains onto Glass

Improving light transmission posed a significant technological challenge that would solve the problem of long exposure times. Patents document the research and effort Louis Lumière invested in creating a device that would increase transparency. He ultimately settled on a press, described in the patent as follows:

“The plate, covered with a layer of grains, is placed on a perforated metal table. A vacuum created in the chamber beneath secures the plate firmly in place. The table, along with the plate, then moves under the operating part of the press. One part of a horizontally positioned lever, approximately 7 cm long, presses against the surface being compressed. The lateral movement of the rod, resembling a windshield wiper, produces a rolling action from edge to edge of the plate. The speed at which the plate moves under the press is set to ensure a uniform result.”

Today, only one of the eight presses from the Monplaisir factory remains in operation. It has greatly contributed to understanding its function and was designated part of France’s industrial heritage in 1995.

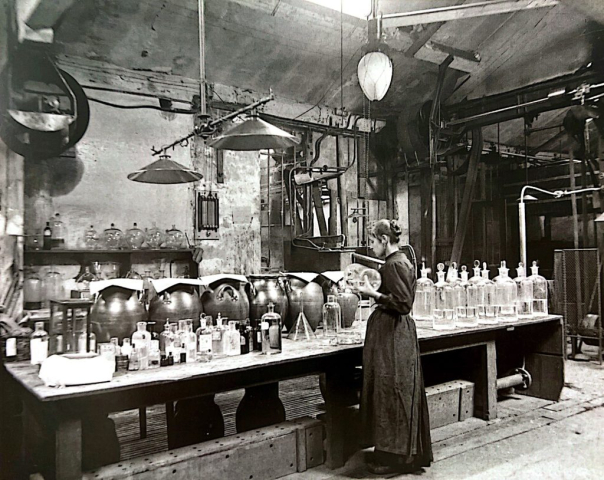

- Fourth Challenge: The Photosensitive Layer

Louis Lumière already had considerable experience in this area. The photosensitive layer was based on the well-known silver-bromide plates—Étiquette Bleue, Étiquette Violette, and Sygma—on which the Lumière factory had built its reputation. The quantities of various substances—gelatin, potassium bromide, potassium iodide, ammonia, and silver nitrate—were adjusted to the reversal development process, which results in a transparent positive image. The emulsion needed to have certain characteristics that regular emulsions did not. It had to be very fine, with particle sizes around 0.6 microns, rich in silver bromide to prevent light diffusion, and it needed to be uniform and responsive to all light spectra. It had to be sensitive to violet, green, and orange light. To achieve this, pigments were added to increase the sensitivity of silver halides across a broader range of the colour spectrum.

Slow Decline

By 1930, the unique characteristics of Autochrome plates, such as colour density and texture, had started to seem outdated, leading to a gradual decline in sales. In 1931, Filmcolor was introduced to the market as a replacement for Autochrome plates. It had much higher sensitivity and eliminated the need for a glass substrate, which didn’t significantly alter the visual quality of the final product. The heavy and fragile glass was replaced with a piece of flexible cellulose nitrate, a material that had advanced significantly with the progress in motion pictures. The Lumière brothers, the architects of the company’s early success, were no longer involved in Monplaisir, having left the factory in 1925. Henri Lumière, Auguste’s son, took over the family business in 1924/25, only to encounter significant financial difficulties. Between 1932 and 1933, the increase in imports of cameras and materials from abroad had a devastating impact on the French economy. Distributors and manufacturers were disconnected, and the influx of foreign photographic goods became inevitable. In 1934–1935, the economic crisis, which had not previously affected photography, became evident. In this environment, the release of Filmcolor in 1931 did little to restore the Lumière company’s position in the colour photography industry. The idea was doomed to failure, and the company did not invest in the new technology necessary for the future of colour photography.

The decline of additive synthesis techniques was expected, especially with the advent of colour films based on subtractive synthesis. These were developed in Germany by Agfa and in America, where Eastman Kodak introduced Kodachrome in 1935. Subtractive colour systems replaced all three-colour systems developed in the early 20th century and dominated the field until the end of the century. In England and America, where the technology for colour photography was already well developed, the transition to the subtractive system was swift. This evolution can be traced through illustrations in National Geographic magazine. In less than five years, National Geographic photographers had fully transitioned to Kodachrome, abandoning the colour screens that had introduced colour photography to the magazine. By around 1955, the last additive plates were produced in the former Lumière factory. At that time, the company sought to shift to chromogenic processes and began distributing Telcolor colour negative films, manufactured by the Swiss company Telko. However, this effort failed in competition with Kodak and Ansco. The Lumière company continued to operate independently for a few more years, during which time the European photographic industry began to flourish in the field of colour printing.

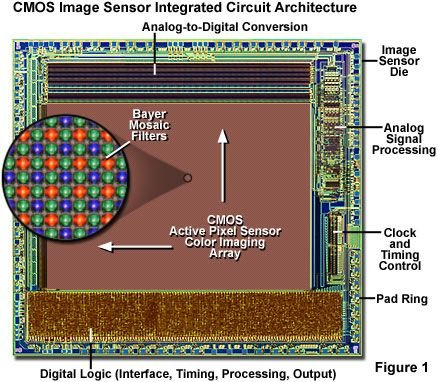

The broader public’s shift to colour photography occurred in the 1960s, as colour film became better and easier to use. The sensitivity of materials increased significantly, colour printing was simplified, and slides, which made it easier to present photographs, became increasingly popular. By the 1980s, the chromogenic process had become the most popular photographic medium, nearly replacing the black-and-white market. However, microscopic colour screens for displaying colours did not disappear entirely. Between 1985 and 2001, the Polaroid Corporation released 35mm instant films called PolaChrome, which featured a screen composed of fine lines in red, blue, and green.

The Legacy of the Lumière Brothers

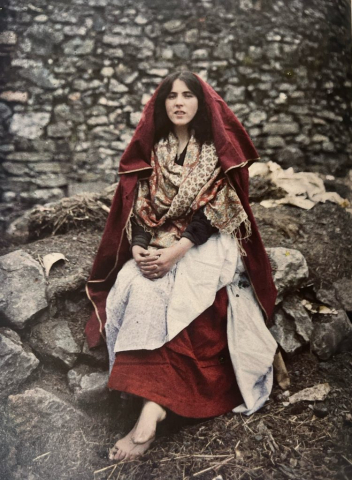

The Lumière brothers not only pioneered a new dimension of colour photography but also made significant strides toward creating the ideal photographic system that combined motion, colour, and depth. Over 25 years, Louis Lumière, in particular, with his innovations in cinematography (motion), Autochrome plates (colour photography), and photostereosynthesis (a process for 3D photography introduced in 1920), opened a window into the future. Louis was an exceptional innovator and determined engineer who consistently succeeded in transforming ideas into innovations and industrializing the products. Although Autochrome never turned a profit, the Lumière company survived by selling black-and-white films, whose profits funded the development of colour photographic materials. In return, Autochrome brought the Lumière brothers worldwide fame and excellent promotion. Thanks to Louis Lumière’s determination and the enthusiasm of Albert Kahn, we now have a unique colour documentation of a world (Archives of the Planet), customs, and cultures that no longer exist.

The dominance of digital photography in the 20th century marks the return of three-colour screens, now embedded in most digital cameras. Their electronic sensor structure closely resembles the three-colour mosaic of dyed starch grains on an Autochrome plate. The renewed commercial success of additive colour systems is, in a way, an echo, reminding us of Louis Lumière’s visionary approach and the industrial genius of the Lumière brothers.

The Lumière brothers’ development of the Autochrome process revolutionized photography, introducing vibrant color to a previously black-and-white world. Their innovative use of dyed potato starch grains and complex production methods led to the first commercially successful color photography technique. Although surpassed by modern methods, Autochrome remains a testament to early 20th-century ingenuity and a foundational step in the evolution of color photography. In upcoming blog posts, we’ll explore the detailed process of preparing an Autochrome plate, revealing the fascinating steps behind this groundbreaking innovation.

Well put together blog post Nejc

Easy to read and very informative

Thank you 🙂

I am fascinated by the look of autochrome. Have you ever tried to make a plate?

I did for my bachelors degree 🙂

Very interesting and Informative – Thank you.