The Evolution of Color Photography: From Black and White to Vibrant Hues

Today, we take colours for granted. Capturing the vibrant hues of nature in photographs is so effortless in the digital age that we rarely ponder how it works and how it came to be.

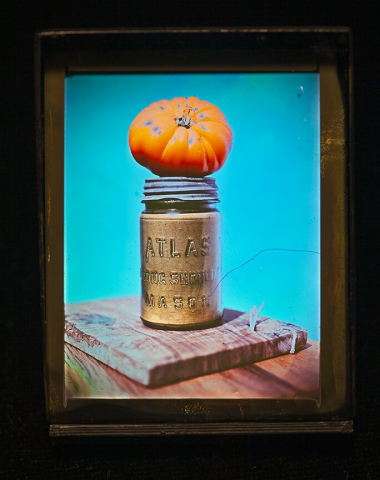

My interest in the history of colour photography was non-existent until I encountered an autochrome plate. Its beauty and mystery captivated me instantly. The colour screen, a mosaic of microscopic dyed grains of potato starch, creates a colour photograph. I couldn’t fathom how something that sounded so simple could work so brilliantly. When choosing a topic for my undergraduate thesis, the choice was clear. I decided to explore the first commercial three-colour technique known as autochrome. I aimed to walk the path that left many empty-handed and brought prosperity and the realisation of bold dreams to a few innovative and brave individuals.

I will approach my research systematically, dividing this series of blogs into historical, theoretical, and practical parts. The first part will delve into the fascinating history of colour photography and the science that predates the autochrome plate, both of which contributed to its discovery. It’s hard to imagine the intense desire for colour when the photographic world was entirely black and white.

The main section will focus on the autochrome plate from its invention and operational principles to its industrialisation. The Lumière brothers, who realised their dreams with the autochrome plate, made significant advancements in the photography and film industries through their life’s work.

In the conclusion of this series, I will engage in my favourite practical part, attempting to create my own autochrome plate using the knowledge I have acquired. This feat has been achieved by only a few to date. I will compare the original manufacturing processes of all components with my experiences, ideas, and solutions that emerged during the process. I will compare the manufacturing processes I followed in 2018 for my bachelor’s degree to my experiences, ideas, and knowledge that emerged during the last few years when I have delved deeper into the dry plate manufacturing processes.

The main goal of my work is to present autochrome in the simplest and most understandable way possible, using written and visual material. I believe that its technical complexity, despite its importance, often pushes it into the shadows of other techniques, which it certainly does not deserve.

The Birth of Colour Photography

1. The Concept of Color and Color Photography

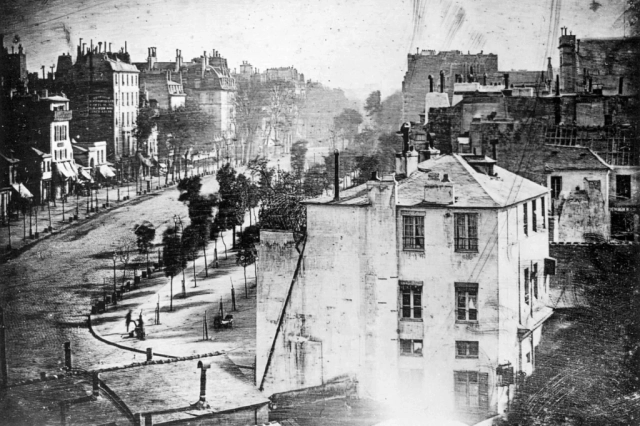

The history of colour photography is a vast and intriguing field, mainly due to the continuous intertwining of art and scientific discoveries. The quest for colour dates back to 1839 when Louis Daguerre announced the first commercially successful photographic technique, known as daguerreotype. Although it was a black-and-white technique that amazed audiences, it left a lingering question. People wondered where the colours, so vividly perceived by our eyes and extensively used by painters of the time, had disappeared in these precise reproductions. This need for colour was beautifully described by writer Wolfgang von Goethe in his book “Theory of Colours” with the quote: “Everything that lives strives for colour.”

Until the end of the 19th century, many attempted to solve this enigma but failed. In the realm of physics, several discoveries were made by the mid-19th century that are crucial for understanding colour. The first theory on colour was conceived by Aristotle, who believed that colour was sent to Earth from the heavens in the form of sunlight. He proposed that all colours originate from white light and black darkness, which are intrinsically linked to the four earthly elements (water, air, earth, fire). His beliefs persisted for over two millennia until Isaac Newton, in 1666, demonstrated the existence of the colour spectrum by refracting light through a prism. Today, this branch of science is known as spectrophotometry.

The transfer of this knowledge to art is largely credited to J.C. Leblon, the father of colour printing using the primary colour method, which we know today as the additive colour system. Physics undoubtedly contributed significantly to the understanding of colours, but the challenge was in transferring this knowledge to the photographic medium, which required knowledge of chemistry. Chemistry as a discipline was not well-established at the time and was only gaining recognition in the 19th century. The issue was not so much with photographic chemistry but primarily with the acquisition and synthesis of dyes. The first aniline (synthetic) dye was accidentally created by William Henry Perkin as a by-product of a laboratory experiment, leading to the development of many others. Despite the efforts of photographers, scientists, and wealthy patrons, public pressure continued to mount. Most photographic innovations of this period were more often the result of luck and numerous experiments than of established knowledge.

2. Hand-Coloured Photography

Due to limited technical knowledge, photographers found subjective methods to add colour to black-and-white photographs. Initially, they simply toned them in various predominantly earthy shades (sepia). Soon after, blue appeared in the form of cyanotype. All these methods were purely aesthetic. The first technique that actually aimed to display real colours was hand-colouring. Hand-colouring involved adding colour to black-and-white photographs using various artistic techniques such as watercolours, oil paints, crayons, pastels, and more. In 1842, Richard Beard was the first to patent a technique for hand-colouring daguerreotypes, which many photographers imitated. Hand-colouring daguerreotypes was an extremely demanding task, as careless application of colour could remove the sensitive silver particles on the polished non-absorbent metal plate.

One must not overlook the effort and craftsmanship required to create such coloured photographs, which, compared to previous methods, brought much closer to real colours. However, significant deviations occurred in details, which are one of the main qualities of photography. Due to this inaccuracy, hand-colouring transformed the image from a photograph into an artistic painting. Despite this issue, similar techniques were used for many years even after the first colour photographic techniques had already appeared on the market.

3. Direct Colour Photography

In the first decade following the announcement of the daguerreotype, the primary goal was to find a substance capable of capturing all the colours in the visible spectrum to create colour photography. The first candidate was silver chloride, which was the main component of many techniques at the time, such as salted paper and albumen paper. To demonstrate this, in 1810, Thomas Johann Seebeck conducted Newton’s prism experiment, placing paper coated with a silver chloride emulsion on the other side. He actually obtained not just uniform greys, but a greyscale representation of the colour spectrum. Most of these experiments resulted in approximations of the colour spectrum.

The first real demonstration of the colour spectrum using a direct method was achieved in 1848 by Edmond Becquerel, a professor at the Paris Museum of Natural History. Despite two major obstacles—long exposure times and the inability to fix the photograph, which eventually darkened and disappeared—Becquerel’s heliochrome plates were the first successful achievement in capturing natural colours with light-sensitive materials.

Following this, there were numerous more or less successful attempts until 1891 when physicist Gabriel Lippmann elegantly solved the problem of indirect photography with a method called interference photography. Unlike other innovators who carefully guarded their discoveries, Lippmann did not patent his new technique, yet he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1908 for this discovery. Several parallels can be drawn between the interference process and the autochrome plate. One of them is the insertion of the plate cassette into the camera, as both involve turning the cassette with the glass forward so that the light first passes through the glass and then reaches the emulsion. Unfortunately, the manufacturing processes for this technique were extremely complex, as was the presentation of the photographs themselves, since the colours only appeared at a specific angle. Due to these limitations, interference photography did not become widely adopted.

4. Indirect Colour Photography

Indirect colour photography was most prominent in the second half of the 19th century. It was driven by the incredible realism achieved through various techniques, particularly those of colour engraving. After 1710, Dutch printer Jacob Christoph Le Blon selected three of Newton’s primary colours (blue, yellow, and red) and used them as printing inks in mezzotint plates. The limited selection of pigments and impurities at the time resulted in lower colour quality, but the level of realism amazed people. Later, psychologist Thomas Young named these three colours as primary colours based on the anatomy of the human eye. This theory was soon further enhanced by Hermann von Helmholtz, who explored the psychological nature of the three primary colours in greater detail.

These discoveries laid the foundation for the development of three-colour photographic processes. These techniques operated in various ways, but all followed the same principle. The human eye cannot detect individual wavelengths of light in the visible spectrum; instead, it perceives a combination of different wavelengths and converts them into colours. Helmholtz demonstrated this by layering and projecting three differently coloured photographs, and this layering process is called additive synthesis. Adding equal amounts of the three additive primary colours results in white light.

A clear proof that these theories work in practice was achieved by James Clerk Maxwell when he created the first three-colour projection. His experiment connected analysis and synthesis, both necessary steps for producing three-colour photographs. Maxwell’s colour synthesis was highly innovative and surprisingly successful for its time, considering all the technical challenges, but it did not lead to a practical method for colour photography.

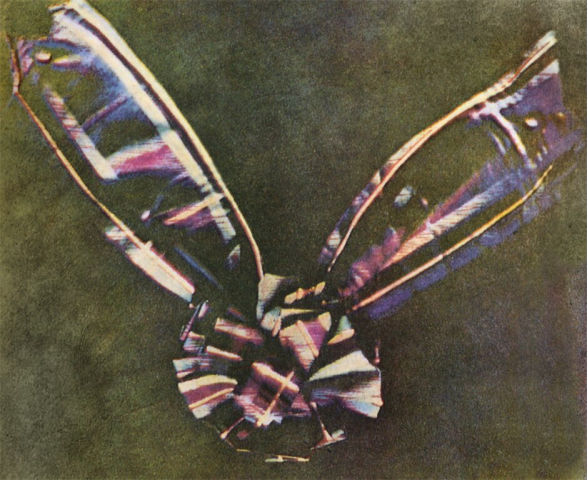

The practical application was simultaneously achieved in 1869 by Louis Ducos du Hauron and Charles Cros. Although the two gentlemen had never met before, their theories were very similar, but Hauron was the first to put it into practice and announced the first colour photographs on paper made by the heliochrome process. The photograph is created using three monochrome negatives, which are converted into positives of three colours (purple, yellow, and blue) through the process of dichromated collodion. Upon announcement, there was great excitement about the new technique, but similar to interference photography, the enthusiasm quickly faded due to the difficulty of the process and criticism.

Conclusion

The journey of colour photography in the 19th century was marked by numerous attempts and significant breakthroughs. From Jacob Christoph Le Blon’s pioneering work in colour engraving to James Clerk Maxwell’s innovative experiments with three-colour projection, each step brought us closer to the vibrant realism that colour photography promised. Although early techniques faced many challenges and limitations, they laid the essential groundwork for future advancements.

In the late 19th century, the foundational theories and experiments in colour photography culminated in practical applications by pioneers like Louis Ducos du Hauron. Their efforts proved that capturing natural colours on photographic material was possible, albeit with complex and labour-intensive methods. Despite the initial excitement, these early techniques were often met with criticism and practical difficulties, delaying the widespread adoption of colour photography.

As we move forward, the stage is set for the introduction of the autochrome technique, which would revolutionise colour photography. In the upcoming blog posts, we will delve into the details of autochrome, exploring its development, principles, and impact on the world of photography. Stay tuned as we uncover the story of how autochrome brought the dream of true colour photography closer to reality, transforming the art and science of capturing the world in vibrant hues.

Fascinating!

Thank you Blake 🙂

Fascinating.

I taught photo history for several years, and am still learning from you!

Looking forward to your next installment on the Autochrome process.

Thank you Hans 🙂

Really interesting and fascinating. Eagerly awaiting for more.

Thank you 🙂